Which is a Disease ?

Which is a Disease ?

The ILO Report on Japanese Karoshi

The ILO Report on Japanese Karoshi

The Japanese Company system is often seen as a possible model of a

democratic and participatory workplace. However, the ILO World Labour

Report of 1993 showed us, that Japanese workers suffered from heavy

stress associated with long working hours, and even from Karoshi

(death from overwork). The ILO report concluded that:

"Stress has become one of the most serious health issues of the

twentieth century --- a problem not just for individuals in terms of

physical and mental disability, but for employers and governments who

have started to assess the financial damage."

"Job burnout is frequently associated with people who have become

'workaholics', working up to 80 hours a week. Such long hours can

strain the physical system even though the damage may not be evident

until later. Nor is there any evidence that the working long hours

will produce a corresponding increase in output. Japanese office

workers, for example often stay at their desks to demonstrate loyalty

to the company. As measured by the goods that can be bought for one

hour's labour, productivity is much higher elsewhere --- 46 per cent

higher in France, for example, and 39 per cent in Germany."

"In Japan this issue has been brought to a head recently by claims

related to the karoshi --- death from overwork. The Japanese work

longer hours than most other industrial nations: officially 2,044

hours in 1990 (compared with 1,646 in France, for example). In fact

the working year is generally much longer because of unpaid 'service

overtime'. A survey by Keidanren, a federation of employers'

organiza-tions, indicated that 88 per cent companies rely on such

overtime. Many Japanese bank officials, for example, work 3,000 hours

per year --- the equivalent of 12 hours a day for 250 days. And a

survey by the Institute for Science of Labour indicated that the

number of hours worked at one major insurance firm had risen from

nine hours a day 15 years previously to 11 hours 20 minutes in

1991."

"Such long hours inevitably take their toll. One psychiatrist in 1992

reported, for example, that the number of patients consulting him for

stress problems had quadrupled over the previous ten years. According

to Dr. Tetsunojo Uehata (who coined the word Karoshi), the problems

first emerged at the end of 1970s when Japanese companies cut their

payrolls in response to the oil crisis and increased the load on

employees."

(ILO, World Labour Report 1993, Geneva 1993, p.65,67)

In fact, the actual working hours of manufacturing workers in

Japan, 2,124 hours per year in 1990 according to official statistics,

were approximately 500 hours longer than in France or Germany. This

comparison, however, is based only on official statistics. As the ILO

report suggests, real working conditions in Japan should also reflect

the so-called service overtime work (unpaid overtime work), the

gender and company-size gaps, the team-based competition, the

weakness of trade unions, and company-oriented governmental

regulations.

I would like now to discuss such issues related to the Japanese

workplace and present the idea of ergology, as an alternative to

ergonomics, similar to the alternative concept of ecology over

economics.

Which is a Disease ?

Which is a Disease ?

The economic growth of the 20th century has been so tremendous

that while great material productive forces have been created, the

ecological environments of the earth are rapidly being destroyed. The

tempo of Japanese development has, likewise, been exceptional. Many

business managers and politicians abroad admire the achievement of

Japan's successful development, describing it as a miracle, and fear

that this development may bring about the Japanization of their

country.

Certain economists sometimes liken economic growth to a healthy body,

and in adopting this approach diagnose stagnant growth as a disease.

These economists coined the terms, 'British Disease' to describe the

pressure on Britain's economy caused by workers' wage increases,

'Swedish Disease' to describe Sweden's welfare burdens, and recently

'Korean Disease' to describe the decline of diligent work ethics as a

result of the marked increase in middle class workers in Korea. The

term 'Japanese Disease' has now been applied to describe the current

economic situation in Japan following the collapse of the bubble

economy caused by necessary restructuring of Japan's economic system

and adjustment to meet international policies.

However, one of the most important questions we must ask ourselves at

this point is whether this 24 hour working rhythm, diagnosed as

healthy by western practitioners, is not really a disease. Would

oriental or Muslim practitioners make the same diagnosis as their

western counterparts ? Is not the golden age of economic growth which

western medical scientists diagnosed as _h_e_a_l_t_h_y surely a

disease, due to the accumulation of stress at work and symptoms of

arteriosclero-sis that it has thus far produced ?

In drawing our conclusion we should perhaps consider whether a

stressful working life with little free time that may bring great

material gain is more healthy than a simple but stressless life with

a comfortable amount of free time.

This paper will examine these questions by comparing working

conditions in Japan with conditions in other countries, and by an

examination of the standard of economic democratization based on

ecological and human ergological criteria as opposed to industrial

economic or ergonomic criteria.

What is "ergology" ?

What is "ergology" ?

The word "ergology" may be new for some present here today.

"Ergology" is derived from the Greek word "ergon", which means work

or labour. The study of ergology originated in Germany, but

development of this field has essentially taken place in Japan. At

the beginning of the 20th century, a famous German biologist, Dr.

Ernst Heinrich Haeckel, named the physiology of nature "ecology", and

the physiology of human beings "ergology".

In Japan, the word "ergology" was introduced by human

anthropolo-gists in the 1950s at the beginning of Japan's so-called

'miracle' period of growth. During the rapid economic growth of the

1960s, Japanese people faced serious environmental pollution and many

indust-rial injuries.

In 1968, Japanese natural scientists, concerned about the trying

working conditions brought about by this rapid industrialization,

formed a small academic society dedicated to the study of Human

Ergology. Thereafter, the society expanded to form a nationwide

research group whose aim was to study ideal working _r_h_y_t_h_ms and

conditions from a humanitarian perspective. The group's work involved

such things as measuring the working tempo and _r_h_y_t_h_m of

factories by employing the circadian _r_h_y_t_h_m theory, and

bringing about an awareness of the vocational diseases brought on by

long working hours and the shift work system.

The association today has approximately 500 members belonging to

various professions, including anthropology, biology, sports science,

medicine and industrial sociology. A quarterly English journal

entitl-ed "Asian Human Ergology" is also published by the association

in Tokyo and is jointly edited with the East Asian Engineering

Associa-tion.

The question I would like to raise at this point is why Japanese

natural scientists have this concern with ergology ? The answer, in

short, is that this interest clearly stems from the great change in

Japan's social environment which occurred during the period of rapid

economic growth. The rapid and unregulated industrialization of the

1950s and '60s brought with it environmental pollution and disease

such as Minamata-disease and Itai-itai-disease, problems conventional

economic theory was not equipped to treat.

Some humane economists adopted the new theory of ecology, search-ing

with natural scientists and medical doctors for solutions to urban

air pollution. Further, a group of lawyers created a new concept in

human rights to defend victims of pollution, the right to

environment.

Moreover, Japanese working people also suffered a high degree of

industrial injury and vocational disease in factories as well as in

offices. Conventional western ergonomics, or human engineering, also

treated the working environment, but it examined only economic

efficiency and productivity.

Ergology was originally a part of ergonomics, but it diverged in

order to analyse elements of industrial labour in terms of the more

essential criteria of physiology and work-science. Ecology examined

environmental problems associated with the production cycles of

_o_r_t_h_o_d_o_x economic theories, air pollution and waste cycles

for example. Ergologists, likewise, sought to apply such theories,

but only in terms of the natural and social limits of human

labour.

Ergologists now concern themselves with a number of topics related to

working conditions in Japan, such as office design, the speed of

factory beltconveyers, the decline of eyesight resulting from

computer usage, and of course the problem of Karoshi, death from

physical and/or mental exhaustion associated with the long hours and

demanding work of Japan's company-centered society.

What is Karoshi ?

What is Karoshi ?

Perhaps many of you are familiar with the relatively new Japanese

word, 'Karoshi'. It is now in use not only in Japan, but also in

advanced capitalist countries, just like the words KANBAN, KEIRETSU,

NEMAWASHI and KAIZEN. The word Karoshi has come to symbolize Japan's

workaholick society.

Karoshi is a socio-medical term used particularly in applications for

workers' compensation, especially in cases of cardio-vascular disease

brought on by excessive workloads and occupational stress. Dr.

Tetsunojo Uehata, who coined the word Karoshi, has defined it as "a

permanent disability or death brought on by worsening high blood

pressure or arteriosclerosis resulting in diseases of the blood

vessels in the brain, such as cerebral hemorrhage, subarachnoidal

hemorrhage and cerebral infarction, and acute heart failure and

mycardial infarction induced by conditions such as ischemic heart

disease (IHD)" (T. Uehata, A Medical Study of Karoshi, in, National

Defense Counsel for Victims of Karoshi, KAROSHI, Mado-sha, Tokyo

1990, p.98).

Although there are no official government statistics on Karoshi in

Japan, the word Karoshi has been widely used particularly by lawyers

who have consulted victims through a "Karoshi Hotline Network"

established in 1988. Lawyers on the National Defense Counsel for

Victims of Karoshi estimate that, annually, about 10,000 workers are

victims of Karoshi, a figure similar to the annual number of deaths

due to motor vehicle accidents in Japan.

Data received by the "Karoshi Hotline Network" from June 1988 to June

1993 have been compiled into Table 1. The victims of Karoshi came

from various occupations, were both male and female, as well as

bluecollar and whitecollar workers. The three occupations which

figured highest in the data were drivers, journalists and machinery

workers. However, recently bank officials, school teachers,

construc-tion workers, and foreign migrant workers have begun to

figure more prominently in the data received by the Network.

Directors and managers, including some Presidents of big companies,

also accounted for a number of the cases reported to the Network.

Table 1 Summary of 3,132 Cases reported to the Karoshi Hotline Network from June 1988 to 1993

|

|

1 Contents of Consultation |

Total |

3.132 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Workers' Compensation |

2,265 (72.5 %) |

|

|

|

(Death Cases) |

(1,466)(47.0 %) |

|

|

|

Health Care |

797 (25.6 %) |

|

|

|

Others |

59 ( 1.9 %) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 Clients |

Total |

3,062 |

|

|

Workers |

633 (20.7 %) |

|

|

|

Wives |

1,549 (50.6 %) |

|

|

|

Other relatives |

560 (18.3 %) |

|

|

|

Trade Unions |

32 ( 1.0 %) |

|

|

|

Others |

288 ( 9.4 %) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 Age |

Total |

3,062 |

|

|

under 30 years old |

197 ( 6.5 %) |

|

|

|

30-39 years |

362 (11.8 %) |

|

|

|

40-49 years |

794 (25.9 %) |

|

|

|

50-59 years |

797 (26.0 %) |

|

|

|

over 60 years old |

174 ( 5.7 %) |

|

|

|

D.K. |

738 (24.1 %) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 Sex |

Total |

2,265 |

|

|

Male |

2,136 (94.3 %) |

|

|

|

Female |

102 ( 4.5 %) |

|

|

|

D.K. |

27 ( 1.2 %) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 Occupation |

Total |

2,265 |

|

|

Director |

96 ( 4.2 %) |

|

|

|

Manager |

454 (20.0 %) |

|

|

|

Manufacturing Worker |

572 (25.2 %) |

|

|

|

Office Worker |

491 (21.7 %) |

|

|

|

Driver |

220 ( 9.7 %) |

|

|

|

Technical Worker |

179 ( 7.9 %) |

|

|

|

Governmental Employee |

160 ( 7.1 %) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 Name of Disease |

Total |

2,265 |

|

|

Cerebral hemorrhage |

363 (16.0 %) |

|

|

|

Subarachnoidal hemorrhage |

372 (16.4 %) |

|

|

|

Cerebral thrombus, infarction |

149 ( 6.6 %) |

|

|

|

Myocardial infarction |

225 ( 9.9 %) |

|

|

|

Heart failure |

393 (17.4 %) |

|

|

|

Others |

763 (33.7 %) |

|

Long working hours

Long working hours

Why is the incidence of Karoshi so high in Japan ? The main reason is clearly related to the disproportionately longer working hours in Japan. According to an official international comparison with other advanced countries conducted by the Ministry of Labor, Japanese working hours per year are about 100-200 hours more than in the US or in Britain, and 400-500 hours more than in Germany, France or North European countries (see Table 2).

Table 2 International Comparison of Actual Working Hours (estimated values for 1990, limited primarily to workers in manufacturing and production industries)

|

COUNTRY |

Hours actually worked 1990 |

1979 |

1970 |

Overtime work1990 |

Days worked 1990 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Japan |

2,124 |

2,159 |

2,269 |

219 |

247 |

|

United States |

1,948 |

1,907 |

1,913 |

192 |

226 |

|

United Kingdom |

1,953 |

1,886 |

1,939 |

187 |

218 |

|

Germany (West) |

1,598 |

1,717 |

1,889 |

99 |

208 |

|

France |

1,683 |

1,712 |

1,872 |

-- |

211 |

|

Iceland |

2,016 |

(no data) |

(no data) |

-- |

|

|

Italy |

1,717 |

1,738 |

1,905 |

-- |

|

|

Norway |

1,650 |

1,572 |

1,794 |

-- |

|

|

Denmark |

1,635 |

1,639 |

1,829 |

-- |

|

|

Finland |

1,608 |

(no data) |

(no data) |

-- |

|

|

Netherlands |

1,584 |

1,669 |

1,893 |

-- |

|

|

Sweden |

1,472 |

1,513 |

1,744 |

-- |

|

These official statistics, however, reflect neither the real

situation nor the feelings of ordinary working people in Japan.

Firstly, these statistics are derived from the average working hours

of firms with over 5 employees. However, thereisa significant gap of

working conditions between big campanies and small ones. In Japan we

have many small companies with under 30 employees. In fact, people

working for small businesses comprise about 60 per cent of the

workforce. Further, these workers often work longer hours and harder

than their big business counterparts, as many small business

companies cannot operate on a regular five day work week. Under the

pressure of the subcontract system to big business, these small

companies must often open even on holidays.

Secondly, these statistics were calculated from official figures

received from the various companies. However, Japanese companies

usually regulate official overtime work in order to reduce the cost

of overtime pay. While companies regulate official overtime, they

often demand of their employees what is known as service overtime,

overtime without pay. According to the ILO Report, this overtime can

reach up to 100 hours per month for bank officials.

According to another official survey in which the workers them-selves

were interviewed (by the Management and Coordination Agency of the

Government), the average working hours per year came to over 2,400.

From this figure we can estimate that a worker's average service

overtime is approximately 350 hours per year.

Thirdly, the official statistics do not reflect the difference in

working hours between male and female workers. Female workers in

Japan, for the most part, work only part-time and in a clerical

capacity. These positions do not generally demand the same amount of

overtime as positions held by male workers. If we view only the

statistics for adult male workers as provided by another governmental

source, the actual working hours per year increase to about 2,600,

500 hours more than indicated by official statistics.

Additionally, it is well known that housing is both limited and

excessively expensive in central city areas where the companies are

located. Thus, workers often spend over 2 hours a day commuting from

their homes to their workplaces. A typical Japanese worker leaves

home at 7 in the morning and returns after 11 at night. Some call

this lifestyle "Seven-Eleven".

We thus estimate that 8 to 10 million Japanese workers, or one fourth

of the male workforce, work over 3,000 hours annually, and amongst

them are surely many potential Karoshi victims.

Without official acknowledgement, No policy on

Karoshi

Without official acknowledgement, No policy on

Karoshi

Karoshi is of course a socio-medical phenomenon. It is now so

widely known in Japan that about a half of all Japanese answer that

they (or their family members) feel anxious over the prospect of

death from overwork (The Yomiuri Shinbun, February 13, 1993).

However, curiously enough, there has not been any official

acknowledgement from the government on "Karoshi", which has not

appeared in any of the official papers published by the Japanese

Government. The Annual Economic Survey of Japan, Annual Report on the

National Life for the Fiscal Year, Annual Report on Labour, or Annual

Report on Health and Welfare, were all published without any mention

of "Karoshi".

Japan's Ministry of Labour informally protested to the ILO when the

ILO printed the word "Karoshi" in its 1993 Report, because the

Japanese Government does not formally acknowledge the existence of

Karoshi. One reason given for this is that the Japanese Medical

Science Society has not yet used the term "Karoshi" as a official

cause of death. Medical doctors have up to now used a more neutral

word "Totsuzen-shi (Sudden Death)" instead, as "Sudden Death" can

occur from multiple causes and cannot be defined solely as death from

overwork. Amongst the statistics produced by the Ministry of Health

and Welfare for their annual report, no figures were given for the

incidence of "Karoshi", reflecting the government's lack of policy on

the issue.

Perhaps the reason for the government's failure to acknowledge

"Karoshi" can be traced to the liability they would assume under the

Workers' Compensation Insurance system. If the Ministry of Labour

were to admit death from overwork as an official cause of death, the

Workers' Compensation Insurance Scheme would be put under great

pressure. I should at first map out the general framework of working

conditions under Japanese Labour Law.

The Labour Standards Act without

general standards

The Labour Standards Act without

general standards

The general framework of working conditions in Japan is set out in

the Labour Standards Act, which was revised 1993. It states that the

maximum working hours is 8 hours a day and 40 hours a week. However,

there are many loopholes in this law.

For example, this law cannot be applied to all workers. In some

service sectors (for example, transportation) and small to medium

sized companies, the regulations cannot be applied. As over 64 per

cent of the working population in Japan work for such companies, we

find many "exceptions" to the Labour Standards Act, with people

working in excess of the prescribed 8 hours a day and 40 hours a

week.

Further, there is no official regulation limiting overtime work.

However, it would be advisable for employer and employee

representa-tives, preferably trade unions, to meet and reach

agreement on limits to overtime. Such an agreement would also

facilitate clearer defini-tion and higher statistical accuracy on

working hours. And within the limits on hours set by the agreement,

workers should obey their employers' request for overtime work.

It is well-known that Japanese trade unions are organized at the

company level, and the unions are weak and often agree to things like

limitless overtime work. For example, one agreement stated that,

"overtime work should be limited to no more than 5 hours a day for

males and 2 hours for females", but "in the case of male workers

during 'special busy' times required for production, maintenance or

repair, the limit can be 15 hours a day." This agreement actually

means that the employer can order workers to work up to 23 hours a

day!

Moreover, current overtime pay rates under the Labour Standards Act

are "more than 25 per cent of the normal wage and the premium for

late night work shall be more than 50 per cent of normal wage". This

"normal wage" in the Japanese context excludes things like family

allowance, transportation allowances and bonuses, which play a great

role in the Japanese wage system. For this reason overtime pay rates

in Japan are exceptionally low in comparison with other countries.

Employers however rely on this overtime in order to adapt their

production to current business trends, and thus can generally count

on their workers to be flexible enough to work overtime when

requested.

Thus, we may conclude that the Japanese management system is

protected by government policies which allow employers to arbitrarily

determine their employee's overtime hours.

The ineffective Workers'

Compensation System

The ineffective Workers'

Compensation System

The government has hitherto taken a negative view towards claims

for workers' compensation by Karoshi victims or their dependents.

The basic role of the workers' compensation system is to compensate

victims by providing income and other necessities to maintain them

and their dependents at an acceptable standard of living, with the

further function of attempting to discourage the future occurrence of

similar injuries or diseases by means of its insurance system and

active investigation of working conditions. The criteria governing

compensation coverage, its content and the amounts of funding

allotted to the compensation system, must all be tailored to

fulfilling these goals.

The reality, however, is that the Ministry of Labour seems to be

attempting to restrict the payment of benefits to Karoshi victims.

The Ministry of Labour's criteria for compensation eligibility are

particularly strict, but the Ministry is known to actually be

employing an even stricter formula that appears in a confidential

manual for inhouse use only. There are also administrative barriers

for victims to overcome, such as time-consuming proceedings and the

task of gathering the necessary evidence, a process which proves to

be a tremendous burden on the applicants filing claims. The companies

to which the victims once belonged, naturally wishing to avoid any

publicity which might give them a bad name in the public eye, tend

not to help in a victim's claim for compensation.

The legislation guiding worker's compensation claims in Japan until

1987 provided mainly for drivers in traffic accident, for miners in

cave-in accidents, and for the industrial injuries of machinery

workers, but not for death from overwork. The dependents of a worker,

who died after 24 hours of particularly hard work, were only granted

an insurance payout.

In 1987, the law was revised, but the basic problems still remain.

According to our ergological research, the accumulation of physical

and mental stress due to hard work over a long period of time is a

significant cause of Karoshi. The guideline of new law, however,

states that the only acceptable cases of death from overwork for

which insurance may be claimed are when workers work twice the hours

of a regular working week without a holiday, or triple the regular

working hours the day before dying. Thus, if someone works 5 days

over 16 hours a day but has one holiday and then dies, any claim for

insurance would be unsuccessful. Following the revision of this law,

dissatisfied families of victims and lawyers took their complaints to

court, but they failed to bring about any further revision to the

law.

The number of applicants claiming insurance by reason of Karoshi

annually is about 500, which is only 5 per cent of the 10,000 victims

of Karoshi each year. Further, of those applicants, the number who

make successful claims are only between 30 to 40 per year, that is,

under 10 per cent of the total applications and less than one per

cent of annual Karoshi victims.

Thus, in the eyes of the Japanese government and politicians, there

is no Karoshi problem at all in contemporary Japan. Indeed, official

statistics do not register figures on Karoshi and there seems to be

some deliberate effort on the behalf of policy makers to prevent this

issue from making the government's agenda. This is a typical case of

"non-decision-making" as defined by P. Bachrach & M. Baraz (Power

and Poverty, New York 1970) or of the "concealing mechanism of the

state apparatus" as put forward by Claus Offe (Strukturprobleme des

kapitalistischen Staats, Frankfurt/M 1972).

Five flaws in Japanese Society

Five flaws in Japanese Society

The long working hours of the average Japanese worker also appear

to have some negative ramifications for Japanese society as a whole.

Professor John Dower of MIT once characterized five flaws he believed

to be evident in Japan's society related to Japan's rise to economic

superpower status.

The first of these is "wealth without pleasure". While Japan is a

massive producer it has little time for the consumption of these

products. This production has made the country wealthy, but people

cannot gain pleasure from just their incomes or from the nation's

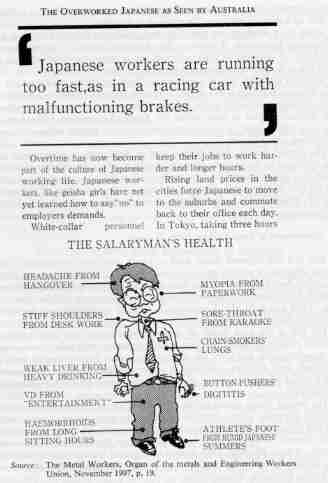

wealth. One Australian trade union publication illustrated a

satirical figure of the workaholic Japanese.

The Overworked Japanese as seen by Australia

(source) The Metal Workers, Organ of the Metals and Engineering Workers' Union, November 1991, p.19.

The second of these flaws is "equality without freedom". In

Japanese society most people earn enough to enjoy a relatively

comfortable standard of living. The gap in salaries between managers

and average workers is perhaps smaller than in the US or other

advanced countries. However, this type of equality is too uniform.

Workers rarely express their own opinions or exhibit any originality

in their work. In fact, this is often discouraged.

This lack of freedom is further displayed during political election

campaigns. During elections it is not uncommon for companies to

'recommend' to their employees certain political parties or

candidates with which that company has some affiliation. Workers who

are reluctant to follow the company's recommendation may be

considered not to be in harmony with the objectives of the company

and even receive a cut in their bonus as a means of re-education. In

short, Japanese workers are expected to act in a uniform manner

without expressing any individuality.

The third flaw is "high level education without originality".

Japanese children attend school approximately 240 days per year, 2

months more than in the US and 3 months more than in France. This

figure is very close to the number of working days per year for

company workers. Japanese children study hard and have a reputation

for exceptional results in international education competitions,

espe-cially in mathematics and history. However, children are taught

a very standardized syllabus, sufficient for entering a good

university and later becoming a good company worker.

The recruitment system of Japanese companies is perhaps different to

that of other countries in that the professional training received at

university in any given field of study has no bearing on a freshman's

recruitment. Rather, a company recruits its new employees based on

the name, or more precisely the ranking of the university they

attended. University rankings are determined by the difficulty of the

institution's entry examination. For this reason school children must

study hard from kindergarten until university entry in order to

ensure a place at a highly ranked institution.

In the battle to win a place at a well regarded university, school

children often attend cramming or supplementary schools known as

"Juku" in addition to their regular schools. This system breeds a

highly educated workforce, but is not conducive to the development of

originality or individual talent.

The fourth of these flaws is "familyism without real family bonds". A

husband may work hard to provide for the well being of his wife and

children, but in doing this, is left with little quality time with

his family. Generally, the working father will only be able to eat

dinner with his wife and children on a Sunday night. Moreover, upon

being transferred to another city, it is common for the father to

leave his wife and children at home and take up a separate residence

(Tansin-funin in Japanese).

Japan has a relatively low rate of divorce, which can perhaps be

largely attributed to the economic dependence of wives on their

husbands' income. Japanese society may, in some terms, be described

as family-oriented, but in actual fact family life has all but

collapsed due to the society's overbearing emphasis on work.

The final and fifth flaw characterized by Professor Dower is

"economic superpower status without leadership in the world". From a

political perspective, due to lack of free time to consider political

or public matters, Japanese people cannot fully utilize the

democratic institutions given to them during the American occupation.

The Japanese government, and politics itself, is too

economy-orientated and fails to address key national and

international political issues.

The average worker shows little interest in diplomatic or

interna-tional issues except when they relate to the domestic economy

or more precisely the well-being of their company. Politics is a

sphere monopolized by professional politicians, not statesmen,

because they have the time to treat public problems and because they

are agents of the business world. However, without free time for

ordinary citizens to debate public issues, there can be no real

democracy.

Four determinants of long working

hours in Japan

Four determinants of long working

hours in Japan

Why is it that Japanese people work so hard ? Are they very

diligent by nature, their national character of collectivism ? I do

not take such a cultural approach. The historical background may be

important, but there is no clear evidence that Japanese people before

the Meiji Restoration in 1968 worked harder than the people of other

pre-industial societies. I will now treat what I believe to be the

four essential factors that determine contemporary Japan's long

working hours.

The first is the weak power of workers' organizations and their

inability to launch successful protests to reduce working hours.

Japanese trade unions are isolated within each large company, and

there are generally no unions for workers in small companies. The

unions were, however, successful in securing higher wages for their

members during Japan's period of rapid economic growth, but they made

no effort to bring about shorter working hours.

The second factor relates to the Japanese company's management

system. Within any given company, strong competition within industry

sectors, among sections within firms and factories, and among

team-based small groups are the engine powering its production

process. This organized competition lies at the heart of Japanese

management practices. I have discussed these aspects of Japanese

management in more depth in my book published in English, entitled

"Is Japanese Management Post-fordist?" (edited with Rob Steven,

Mado-sha, Tokyo 1993).

The third point determining Japan's long working hours is the

non-decision-making by government in regard to working hours. In its

5 year economic plan under the Miyazawa Cabinet, the Japanese

government declared that it would bring about 1,800 working hour

year. However, the government effected no policy or regulation geared

towards restricting overtime work or reducing the incidence of

Karoshi. Industrial relations in Japan are perhaps the most

"free-market" or "non-regulated" sphere of a company's operation,

with only minimal "administrative guidance" from the government.

The fourth point, paradoxically, relates to international pres-sure.

Japanese companies and the government appeared to examine the

prospect of reducing working hours only after attacks from the US and

other western governments who argued against the "unequal competition

in the world economy" that Japan's disproportionately high working

hours was causing. For example, the five-day working-week system of

banks and national universities was adopted only after US-Japan trade

friction reached boiling point. Further, the Miyazawa cabinet's plan

to reduce the annual working hours to 1,800 as a part of their 5 year

economic plan was also a product of international pressure.

However, Japan's integration into the world economy has meant that

bank officials and workers of securities or insurance companies must

keep a constant watch on the world market so that they may adjust to

changes in financial markets and to foreign exchange rate

fluctuations. Such workers, as well as those of trading companies and

transnational corporations must often be prepared to work 24 hours a

day to adjust to the movements in world markets, from the Tokyo, the

New York to the London markets. This need for 24 hours alertness

quite obviously causes tremendous mental stress and can be strongly

linked to the recent increase in young Karoshi victims from banks or

securities companies.

The following is a summary of these alternative proposals.

(1) For overworked workers,

For overworked workers,

Your company will run without your work. Make time to break your

tense work cycle!

Do not work through 24 hours a day! Make sure you give yourself

sufficient free time daily!

Find time to talk with your wife and revive yourself at home with

your children!

Determine your own overtime, rather than have it determined by your

company! After five is your own time!

Do not rely so much on such aids as stamina drinks to get through the

day!

Take a rest before you too become one of the victims of Karoshi!

(2) For housewives,

For housewives,

House work and nursing should be a cooperative effort with your

husband! Divide the household chores!

Dinner should be a pleasurable time for all the family! Please make a

happy household!

Try to ensure that there is good communication between parent and

children!

Make a family culture together with your husband!

(3) For you and your fellow

workers,

For you and your fellow

workers,

Decide with each other on a no-overtime day each week, and negotiate

a regular working cycle! Do not make an agreement that allows

flexible overtime hours! Pressure your union to raise the rate of pay

for overtime!

Attempt to realize your 1,800 working hours per year by such means as

suggesting worksharing schemes!

The employment of more workers under this scheme should allow you to

take annual holidays freely without fear of overburdening your fellow

team members!

Bring the Japanese Constitution into your company! Human rights and

freedoms must be revived at your workplace!

(4) For a comfortable society,

For a comfortable society,

Complete realization of a 40 hour working week by rigid applica-tion

of the Labour Standards Act!

Implement a five-day work week system both at the workplace and at

school!

Restrict any kind of overtime through strong administrative

regulations over working time!

Reform the standard of Workers' Compensation Insurance for Karoshi

victims!

More time at home for men, More time at work for women! Real equality

between men and women begins with the elimination of disproportionate

working hours!

My conclusion is now clear. Democracy in the workplace is heavily

dependent on political democracy. Further, for political democracy,

the elimination of excessive working hours is crucial, at least in

contemporary Japan. Moreover, to realize a free and comfortable

ecological society, we must revise our conception of labour from the

present ergonomic perspective to an ergological one.

GO TO INTERNATIONAL EXCHANGE CENTERÅ@

Å@